Luckily, they gave me a second chance

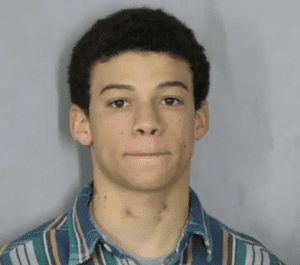

James Elliott - Felon, Scholar & Advocate

A LIFE-CHANGING EVENT

The police pinned me down in my front yard. As an officer placed handcuffs on me, I looked up to see my father standing in our living room, watching my arrest through the bay window. I was nineteen years old.

Just days before, I made the worst mistake of my life. I took part in a home invasion robbery near where I lived with my parents in Newark, Delaware. I was arrested, tried, and convicted for my part as a gunman in that crime. Ultimately, I was sentenced to seven years in prison.

MY TIME IN PRISON

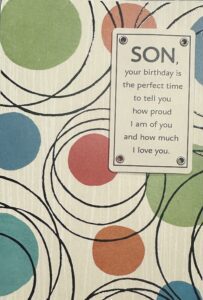

On my 20th birthday, I was in solitary confinement, stuck in a prison cell 23 hours each day. I read a birthday card from my parents through a small window in the cell door – my only tangible connection to the world.

That moment marked a profound turning point in my life. I paced back and forth, thinking about…

All the mistakes I had made

All the ways I disappointed my parents

All the opportunities I had given up

I relived the moments that brought me to the desperate loneliness of a prison cell

GROWING UP

I come from a biracial family; my mother is White and my father is Black. Throughout my formative years, the weight of anti-black racism heightened my academic struggles. I turned to drugs and alcohol to cope.

During my senior year of high school, I stopped attending classes and started selling drugs. I failed to meet the attendance requirements needed to graduate. While my peers walked at graduation and prepared for university, I found myself attending summer school and reluctantly registered at Delaware Technical Community College.

I was driven more by familial expectations than personal ambition. I was never motivated. Just weeks after classes started, I dropped out. Only days later, I took part in the robbery.

EDUCATION

Once imprisoned, I had nothing but time. My mother encouraged me to use those endless hours to read and learn. That’s when I discovered an unexpected catalyst for change: Education. I found solace and purpose in learning. Then I got interested in prison reform. I wanted to help others access education while confined in prison, to see a wider world and opportunities beyond a cell.

When I left prison, I thought my troubles were behind me, but I was in for a shock. It was tough to find a job, any job. When I was rejected from a janitorial post because of my felony record, I faced the overwhelming number of collateral consequences from my conviction. So many roadblocks stood in my way.

A SECOND CHANCE

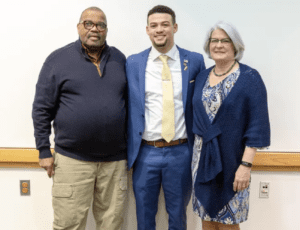

A month after I left prison, Delaware Technical Community College gave me a second chance, allowing me to enroll in classes while still wearing an ankle bracelet. With support from advisors and instructors, I thrived, double majoring in Human Services and Drug and Alcohol Counseling. I became a campus leader and was selected for Phi Theta Kappa, the community college honor society.

As a PTK member, I collaborated with campus administrators to create educational opportunities for people in prison or on parole. My efforts gained national recognition, leading to my election as the first previously incarcerated International President of PTK.

TRANSFERRING TO COLUMBIA

DTCC was my springboard to the Ivy League. After completing my associate’s degree, I transferred to Columbia University. I completed my bachelor’s degree with high honors and was selected as a Truman Scholar, a highly competitive scholarship recognizing my public service work, academic achievement, and leadership.

Seven years after being released from prison, I crossed the graduation stage at Columbia, with my young daughter holding my hand. I’m not finished with my education. I’m applying to law school. Afterward, I plan to become an attorney advocating for social justice and prison reform.

PAYING IT FORWARD

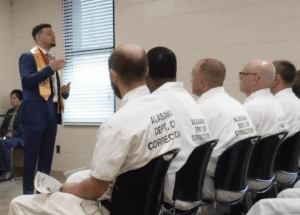

In the interim, I interned with U.S. Senator Chris Coons and worked on legislation to expand Second Chance Pell, which provides higher education grants for incarcerated people or those just getting out of prison.

I am passionate about this legislation because I know ex-offenders who receive higher education are less likely to return to prison. Without learning a trade or earning a degree, it’s nearly impossible for returning citizens to earn a living. That’s when prison becomes a revolving door. But with trade skills or a college diploma, opportunities expand for a life beyond crime. The more credentials you have, the less likely you’ll return to a prison cell.

WHAT A JOURNEY

My journey from Delaware Technical Community College to Columbia University is a vivid testament to the power of second chances and wider opportunities through higher education.

The day my father witnessed my arrest from our living room window seems like a distant echo. Since that horrific day, and because of the second chance I received, I have turned my life around and given my father many joyous occasions to witness.

I can’t wait for him to see what comes next.